Remaking Our Covenants of Life and Death on the Dunes Commons

J. Ronald Engel

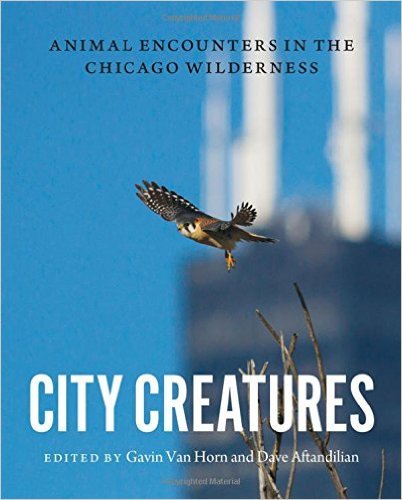

The following passages are excerpts from an essay that appears in City Creatures: Animal Encounters in the Chicago Wilderness, edited by Gavin Van Horn and Dave Aftandian, published by the University of Chicago Press in 2015. These excerpts deal with the history of ERG's deer control efforts, but omit the broader context, both contemporary and historical, in which these efforts have taken place. We encourage readers to read the complete and very lovely essay, available in the book and from the Google Books version online.

I did not expect when we moved to the Indiana Dunes that someday I would be constructing a seven-foot-high deer fence around the perimeter of our property. Nor did I anticipate, as my friend Xhela Mehmeti and I set about driving in the metal posts and attaching the black plastic netting, that the issue of how we should live in right relationship to deer would raise far-reaching questions of war, hunting, predation, and ecology, and lead our community to remake its covenants of life and death on the Dunes commons.

While building the house in 1992, my wife and I had felt nothing but delight when we ran with the carpenters to the window to see the doe and two fawns cautiously making their way through the black oak savanna on which our foundation was set. When the house was ready, we ceremoniously hung on the wall our large brown etching of a coy doe with big seductive eyes by Chicago artist Bronislaw Bak. The deer were all of a piece with our tufted titmouse, trillium, and wild grape vines.

But in 2002, 14 thin and hungry deer were bedded down on our ancient dune ridge. Garlic mustard spread by their hooves had replaced the wildflowers, the understory was cleared up to the browse line (the limit deer can reach when feeding), and birds were scarce. An aerial survey showed 121 deer in the one square mile of the town of Beverly Shores where we lived. Wildlife experts told us that at most 15 to 20 were sustainable.

We were not the only ones who felt under siege. Embraced on all sides by the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, Beverly Shores is truly a blessed community. In 2001, however, when it was clear that the superintendent of the lakeshore was not going to take action on the deer issue, residents petitioned the town council to authorize sharpshooters to make a deer cull. Immediately, in what is now a typical narrative according to Jim Sterba's well-titled book Nature Wars, all hell broke loose. Two groups were formed, one in favor and one opposed. So much acrimony was generated that, one night, in a desperate attempt to find a compromise, the town council voted both to permit residents to shoot deer on their own property and to allow a group of “animal rights advocates and others” to surgically sterilize 75 male deer! Afterward, a member of the pro-cull faction exclaimed: “Is this going to be Beirut on the lake in Indiana?” A representative of the anti-cull faction chimed in: “You people are crazy. Absolutely crazy.”

The vision of the Dunes as a sanctuary for all life drew deeply from many cultural sources, including the notion that a Peaceable Kingdom will come when humans tame their willful egos and spread the Light of loving-kindness to embrace all creatures of the world. In 1913 the Chicago dramatist Kenneth Goodman wrote a masque, “The Beauty of the World,” which climaxed in an exchange of vows between a “friend of the Native Landscape” and a fawn. The friend pledges everlasting protection of the fawn's home and the fawn in reply pledges:

These woods are mine and thine. Thy children's children

Shall find me always here to welcome them.

I pledge to thee and them ever lasting calm,

A refuge from the fret of roaring streets,

Silence and Beauty, Peace and leafy shade …

In 2001 an imaginative story by the Pressley family appeared in the Michigan City Post-Dispatch. It told how a doe named “Beauty” refused an apple when she learned that the town of Beverly Shores might undertake a deer cull. Although it is unlikely the Pressley family ever heard of the Goodman masque, which was last performed in the Dunes in 1948, they were obviously fearful that harming deer would somehow break a personal vow.

One effect of this interpretation of “peace” was to encourage the domestication of the deer. Some residents regularly fed the deer and opposed any legal ban on feeding. Each morning in the winter of 2002, someone dumped a bushel of apples on the side of the street in front of our house. Even more telling were the proposals, encouraged by Dr. Allen Rutberg of the Humane Society of the United States, to inject contraceptives in does—in effect treating the deer as human patients in need of mandatory planned parenthood. The burgeoning deer population was leading some to advance powerfully intrusive disruptions of the reproductive behavior and natural satisfactions of deer. Our town and the rest of the Dunes commons were being turned into a deer park.

Predator and prey rely on one another for life. Where one exists without the other, it is a species out of place, robbed of its necessary evolutionary partners. Since we humans have removed other predators from the Dunes ecosystem, we have become the de facto top predator, with all the responsibilities that such a position entails. We are not going to restore mountain lions and wolves to the Dunes commons anytime soon, so it is up to us to fulfill their roles.

Everything finally rests on whether we extend the covenants of life and death by which we live to include other creatures, or restrict them to humans alone. In covenants we commit ourselves to the well-being of Others in their freedom and individuality and to the relationships between us that have the power to sustain us as a community over the generations. Inclusive covenants involve different obligations to different Others within a common obligation of respect and care for all. Just as our covenantal obligations to different persons—to friends, marriage partners, colleagues, and fellow citizens—differ, so do our obligations to other species. This is something we have only begun to sort out and understand. If we are to take responsibility for deer, to accord them rights, or to feel obligated in some sense as stewards of their welfare, we must include them in a comprehensive covenant that not only respects and cares for them as individuals but also accords with the ecological and evolutionary processes on which their individual and species well-being depends.

If anyone had reason to think of the Dunes as a prelapsarian Eden, it was Bob Beglin. He and his family discovered the town of Beverly Shores by driving up a remote lane one hot August afternoon in 1971 in search of a place where they could change their clothes and take a swim. At the end of the lane, they surprised a couple making love in the woods. Then and there, as Bob liked to tell the story, he knew this was the place where he wanted to live. Bob loved wildflowers. In the 1990s he became alarmed as he noticed flowers disappearing, and he began to correspond with university experts on the impact of deer overpopulation on natural habitat. In 1999 Bob convened a series of educational meetings for the community that enabled us to see how the well-being of the deer population depended upon the well-being of the total trophic or ecological pyramid of the Dunes commons, and therefore how important it was to maintain or restore the integrity of the food chains (including the predator-prey relationships) that link the life and death of soil organisms, plants, herbivores, and carnivores throughout the ecosystem. He also made sure that all sides on the question of how to address deer overpopulation were expressed. There were presentations by representatives of the National Lakeshore, the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and by local conservation, veterinary, and animal welfare and rights groups.

By 2001, however, civil discourse was no longer possible at town meetings, and a series of legal suits and countersuits usurped the public space. In spite of the acrimony, Bob did not give up. He went on to organize a not-for-profit organization, the Environmental Restoration Group, which was dedicated to funding the legal expenses of cull advocates, pursuing research and education on the impact of deer overpopulation on human and deer health, and doing whatever it could—pulling garlic mustard became a favorite pastime—to restore the native plant communities at the base of the commons ecosystem. After seemingly endless debate and a new town election, the group successfully made the case to the town council that a series of annual deer culls by skilled bow hunters could effectively and safely reduce the deer population to sustainable levels.

It was at this point that the deer fence Xhela and I were building took on a much more positive meaning. In effect we were creating an experimental plot. A few seasons after it was erected, the biologist with the Indiana Department of Natural Resources used our property to demonstrate the difference behveen healthy protected vegetation and vegetation exposed to excessive deer browse. By casting the deer issue as a matter that needed to be addressed within the context of the restoration of the full range of ecological interdependencies of the Dunes landscape, the Environmental Restoration Group changed the dynamics of our community and opened the doors to healing. The question became How might we in our current circumstances show gratitude for the blessings of living in this place, comparable to what the first Dunes enthusiasts showed a century earlier? This meant both reaffirming the covenant that had inspired several generations to protect the Dunes (a common aim of pro- and anti-cull advocates alike) and remaking the covenant so as to responsibly embrace the roles of top predator and steward of ecosystem integrity that history and evolution had thrust upon us.

But the Dunes were not the only gift that needed to be stewarded for the future. We had also received the gift of living in a democratic society, where scientific facts could be publicized, alternative courses of action tested, differing moral judgments debated, and the rule of law prevail. In the final analysis, the conflicts we suffered over the deer issue were not something to deplore, but a sign of democracy alive! The deer issue was not a tragedy but an opportunity for us to better learn our place in nature and exercise our covenantal obligations for the health of the political as well as natural commons.

Bob became acquainted with a local bow hunter, Don Dolph, who had intimate knowledge of the terrain of Beverly Shores. Bob and his wife, Arlene, spent many hours sitting at their kitchen table with Don talking about deer. They were astounded by what Don knew about them, almost down to each individual deer family—where they bedded down; when, why, and where they moved; the trails they frequented; their life cycle; when a buck will stand its ground; and just how dangerous a kick by a hoof can be.

Some years later, in conversation with Tom Lane, the current coordinator of the Beverly Shores deer cull, I also learned just how attentive bow hunters are to the lifeways of deer in the local ecology and how challenging the discipline of bow-hunting is. Tom recruits around ten people each year from the Deep River Bowman Club and runs each through a demanding proficiency test at his home. What he is most watching for, he says, is not only how many times they can place a broad-bead arrow in a two-inch circle at twenty yards, or how readily they can leverage a seventy-pound draw on their bow, but how much respect they give to what they are doing.

The heart of the hunt is the heightened awareness of nature it calls forth. My wife and I can relate to this as birders, but only so far. The hunt begins well before daybreak and ends at nightfall, and throughout the entire intervening time the hunter must sit or stand as immobile as possible. Sometimes squirrels will scamper within inches and birds perch only feet away.

“When a deer finally appears,” Tom told me, “I can feel my heart pound and almost believe it is pounding in rhythm with the heart of the deer. Then I must wait until the deer offers a clear, straight shot to its heart or lungs, a vital zone no larger than eight inches in diameter. Sometimes the buck of a lifetime walks away if you don't have a good, straight shot.” The actual killing of the deer is over in fifteen to twenty seconds. The deer may run a few yards, but it will soon slump down on the ground and expire. “The worst thing is to wound an animal that then gets away,” Tom said. “It doesn't happen often. When it does, we do everything possible to track the deer and end its life swiftly.” The Beverly Shores bow hunters examine the internal organs of the deer they shoot in order to judge their health. They pay for the deer to be dressed and made available to a local food pantry. The flesh of the deer must be shared for the hunt to be judged successful.

In 2012, almost a century after the founding covenant to preserve the Dunes commons was made by those who witnessed the "Historical Pageant and Masque of the Sand Dunes of Indiana," another commemorative ceremony was held. This time it was a memorial service for Bob Beglin, who helped teach us how that covenant must be remade if its original intention is to be fulfilled.

From 2012 to 2013, Tom's team of bow hunters took twenty-nine deer in Beverly Shores. Deer culls by bow hunting in Beverly Shores is now a model for other communities in Indiana.

In March 2013, fifteen years since alarms were first raised by local residents regarding the degrading impact of deer overpopulation on the Dunes commons, U.S. government sharpshooters conducted their first deer cull within the National Lakeshore and killed eighty-four deer.

We still have our deer fence. We look forward to the time when the deer numbers finally reach sustainable levels and we can take it down. One fall during rutting season, a doe sprang over the fence, leaving the buck who was chasing her standing outside, head cocked sideways, as if saying to himself, Now I have seen everything! She then leapt back out with graceful ease.

Such adventures are no substitute for what we have lost. We no longer peer from the window in anticipation of a burst of white bounding off through the woods. The forest is no longer so mysterious. It no longer harbors in its shadows creatures whose visage was somehow burned into our subconscious over millennia, creatures our ancestors drew with obvious delight on the walls of caves, bearers of vitalities beyond our ken, who call forth all our senses of alerted sight, hearing, tensed muscles, and patience, our hearts in our throats.

We need the deer and we need them wild. They are an irreplaceable part of the plenitude of being that constitutes our natural and mental worlds. The deer also need us, but they need us to be the ethically responsible, environmentally attuned, and politically self-governing creatures we have the potential to be. These two needs can only be met if we remake our covenants of life and death on the Dunes commons so that war is abolished and ways are found for predation and the full ecological pyramid of life to be sustained.